Note: The following is an excerpt from Donald’s presentation at the Philippine Institute of Civil Engineers (PICE) Singapore Chapter on contaminated land and conducting Environmental Baseline Studies in Singapore. You can visit their website here.

Above: SECS Environmental Director Donald Folkoff (right) with PICE President Christopher Vitug (left).

Introduction

Many years ago, when I was working for a US consultant performing geotechnical work, our clients would often suggest that we conduct an Environmental Site Assessment since our equipment would already be in the field. We would tell them: “Hey, no one is requiring you do to this – this is not legally required”, since we were trying to be savvy and save costs for our customers.

Yet, they would tell us to go ahead and do it because there was an understanding that these regulations could change at any time and they wanted to be ready for it. And lo and behold, it has. I have watched this process from when it began pretty much in the early 1990s through to where it is today, and it has become a given in most construction and infrastructure projects.

Singapore has been no exception – for example, the Jurong Town Council (JTC) makes EBS/ESAs a requirement in their lease agreements. Interestingly, there is no legal definition of contaminated land in Singapore. Instead, we tend to lean on international or well established definitions. The UK defines contaminated land as “land containing chemicals in sufficient quantities to present risk or potential risk to human health or the environment”. The US EPA, on the other hand, adopts a physiochemical definition: soil contamination is either solid or liquid hazardous substances mixed with naturally occurring soil.

Sometimes, it is easy to identify land contamination. The soil may be visibly contaminated, or stained with odour such as petroleum. Assessment, however, is always accomplished by referencing soil and groundwater sample analysis against recognized standards, criteria, guidelines, or screening levels.

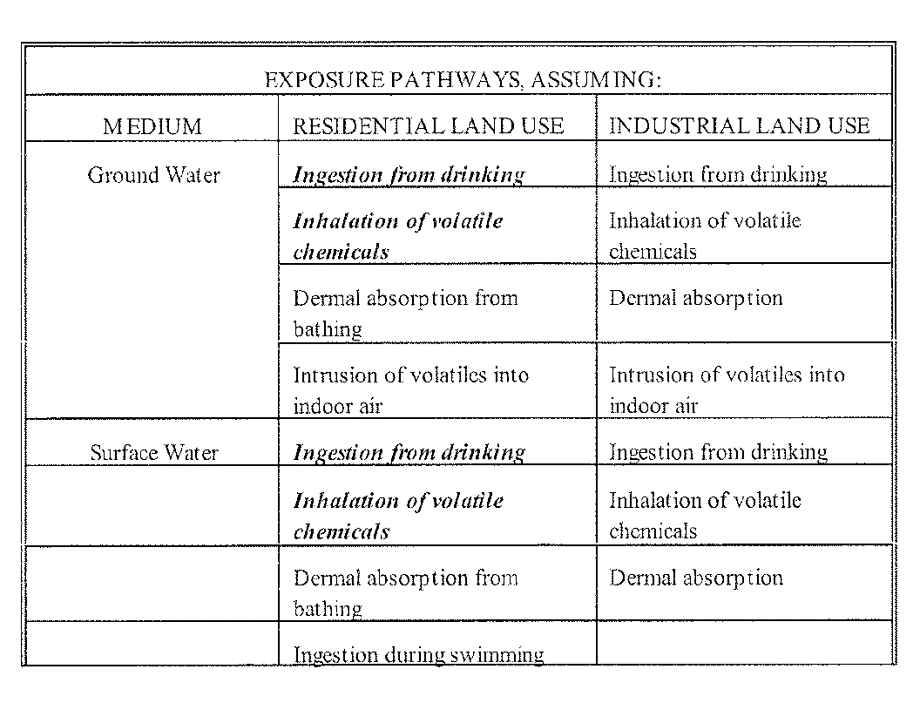

Some standards we use include:

- Dutch target and intervention values (most commonly used in Singapore by governing agencies such as the JTC, NEA, and SLA)

- New Zealand Guidelines for Assessing and Managing Hydrocarbon Contaminated Sites

- USEPA (Region 3), ASTM 1739, 2081 RBCA Petroleum and Chemical Release Sites

- US State EPA (Texas, Florida) and Australian State EPA (Victoria)

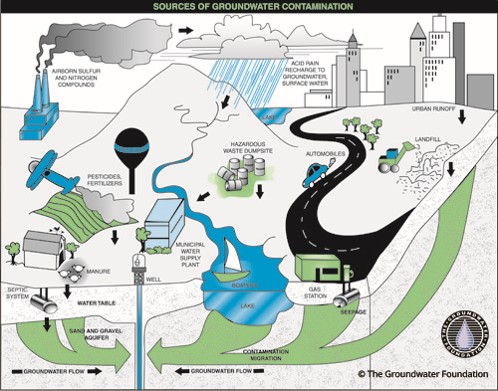

Above: Common sources of groundwater contamination. More information can be found on the Groundwater Foundation website.

How Contamination Happens

Contaminants can be classified as organic or inorganic.

Common organic contaminants include Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) such as benzene in gasoline and trichloroethene metals, or Semi Volatile Organic Compounds (SVOCs) that include herbicides and polynuclear aromatic compounds. This also occurs when there are fuel or oil spills.

Common inorganic contaminants are metals and anions. Metal contamination occur frequently in scrapyards or battery storage, whilst anion contamination can involve nitrogen compounds (e.g. nitrates from leaking sewers) or chlorides (salt piles).

Contamination can enter the groundwater through surface activities (e.g. spill, release, leachate). Once it’s in the groundwater it can form a plume, and it can travel along with the groundwater.

Contaminated groundwater in Site A can, over years, migrate along with the plume to Site B. This makes things complicated because Site B finds their groundwater is contaminated when they do not use any of these chemicals or contaminants in their processes. Detailed analyses are required to determine the source of contaminants in such a situation.

What is an Environmental Site Assessment or Environmental Baseline Study?

And why conduct one?

An Environmental Site Assessment (ESA), or Environmental Baseline Study (EBS) as it is typically known as in Singapore, is a phased approach towards identifying potential or existing environmental contamination liabilities. Essentially, its purpose is to establish the baseline level of potential contaminants in soils and groundwater beneath a site and to assess the extent of contamination of the site if applicable. Details about the three phases of the study can be found in the following section.

Here are three reasons why an EBS or ESA is needed.

Reason 1 – Legal Requirement

In Singapore, an ESA/EBS is legally required as part of Jurong Town Council (JTC) lease agreements which include new leases, transfers, lease extensions, and lease terminations. The Singapore National Environment Agency (NEA) code of practice also requires an ESA/EBS to be conducted when changing land use from industrial to residential.

Reason 2 – Corporate Responsibility

For most companies, particularly MNCs, these studies are conducted in line with corporate policies related to their environmental management, best practices and responsibility, and as protection against future liability in the event of changes to environmental legislation and policies.

Reason 3 – Due Diligence

As explained previously, pollutants can migrate over time from one site to another. Although the land you are leasing or purchasing might not have been used previously for potentially pollutive purposes, contaminants from neighboring sites can enter the soil or groundwater beneath your property. This leads to complex situations where the polluter or the party responsible for remediation might be difficult to identify.

Above: Environmental Baseline Study conducted in Myanmar

Phase I

Environmental Site Assessment/Environmental Baseline Study

The Phase I is a non-intrusive investigation to identify potential contamination sources. The objective here is to identify potential liabilities, and determine the presence of “releases or threatened releases of hazardous substances on a property”.

Work items for the Phase 1 include:

- Initial contact and questionnaire

- Site visit to survey the current use of the property and neighbouring sites, as well as interviews with knowledgeable parties

- Records review of documents related to prior land use, such as chain of title, aerial photographs, topographic maps, public databases, etc

- Regulatory review to examine permits and compliance history for the site and surrounding area

- Review of the geologic, topographic, and hydrologic site features via the use of maps and reports

- Reporting of findings, results, and conclusions – this will allow us to determine if there is a need to undertake a Phase II ESA/EBS.

Phase II

Environmental Site Assessment/Environmental Baseline STudy

The objective of the Phase II is to conduct intrusive sampling and testing to either confirm or deny the presence of potential contamination identified during the Phase I, and evaluate the impact of any potential contamination.

Components of the Phase II include:

- Review of the Phase I – includes the likely sources and types of contamination, physical characteristics of the site, and potential sampling locations.

- The Assessment Program – includes the development and implementation of the Sampling and Analysis Plan (SAP), field work, and laboratory testing. The SAP also includes a Field Sampling Program and an overall QA/QC project plan for both field sampling and laboratory.

- Reporting – compilation and verification of data, presentation of results, and conclusions.

Phase III

Remediation

The Phase III involves additional sampling and testing to further characterize the extent and impact of contamination, and develop a remediation strategy.

Components of the Phase III include:

- Review of the Phase II – evaluation of the Phase II report.

- Develop the SAP- to fully characterize the extent of the site contamination.

- Risk Assessment – Further tier development of RBCA if required with respect to future/present land use options.

- Evaluation of remedial alternatives – assess the appropriate alternatives with respect to feasibility and cost.

Guidance Documents and standards

These are some of the standards and guides we use at SECS:

- ASTM Standard Guide (E1527-05 Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Process)

- ASTM Standard Guide (E1903-11 Phase II Environmental Site Assessment Process)

- State of Connecticut DEP Site Characterization Guidance Document

- NZ Contaminated Land Management Guidelines No. 5 (Site Investigation and Analysis of Soils)

- USEPA Compendium of ERT Groundwater Sampling Procedures

- IAEA-TECDOC-1415 (International Atomic Energy Agency)Soil sampling for environmental contaminants

We also use the Dutch Target and Intervention Values, but this warrants some further discussion.

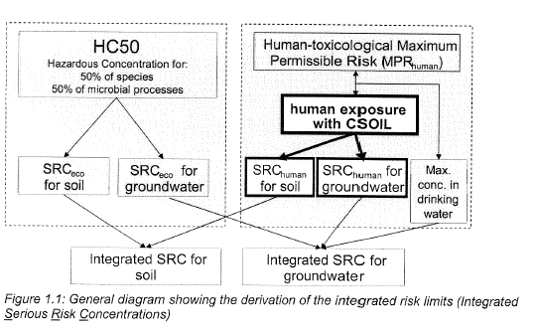

A Quick Look at the Dutch Values

We begin by differentiating between the Target Value and the Intervention Value. In the Dutch policy, Target Values indicate “the level that must be achieved to fully recover the functional properties of the soil for human, plant and animal life.” Levels below these Target Values indicate that the soil and groundwater quality is uncontaminated and safe enough for the most sensitive uses. These are very rigorous standards – it means that the soil or land can be used for any land use, even a childcare centre where children may be playing or digging in the dirt.

The Dutch Intervention Values are where the “functional properties of soil for humans, plant and animal life will be seriously impaired or threatened”. For levels above the Intervention Value, remediation will be required.

The thing to note with the Dutch values is that it emphasizes both human health and eco-toxological factors; that is, it emphasizes not just human health, but plant and animal life as well. Specifically, the Dutch value looks at the level where a substance is harmful to humans and the level where it is harmful to ecology, and selects the lower of the two. For example, copper in soil has a very low intervention value relative to what would be deemed “contaminated”. This is because the intervention value for copper is being determined by its eco-toxological health properties, not its human health properties.

It should be noted that the Dutch have revisited their own standards in recent years, and they have done away with the target values for soil. However, in Singapore, guidance documents still reference the old Dutch standards, such as the Jurong Town Council EBS guidelines and the National Environment Agency’s Code of Practice on Pollution Control.

It is therefore important to consider land-use when selecting a standard. Whilst the Dutch standards are indeed rigorous, there are cases where the more sensitive eco-toxological values may not be as applicable in cases where the main concern is only human health. For example, if we are testing groundwater for industrial use, it would not be logical to apply the more rigorous standards which assume potable use. In such cases, we would defer to other respected standards that fit the actual land use.

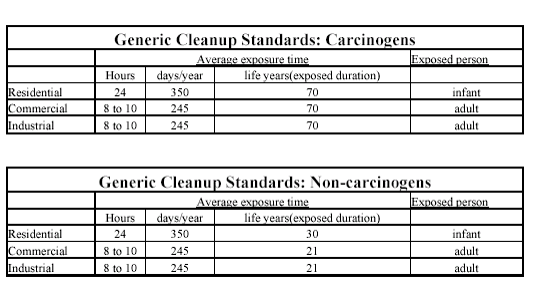

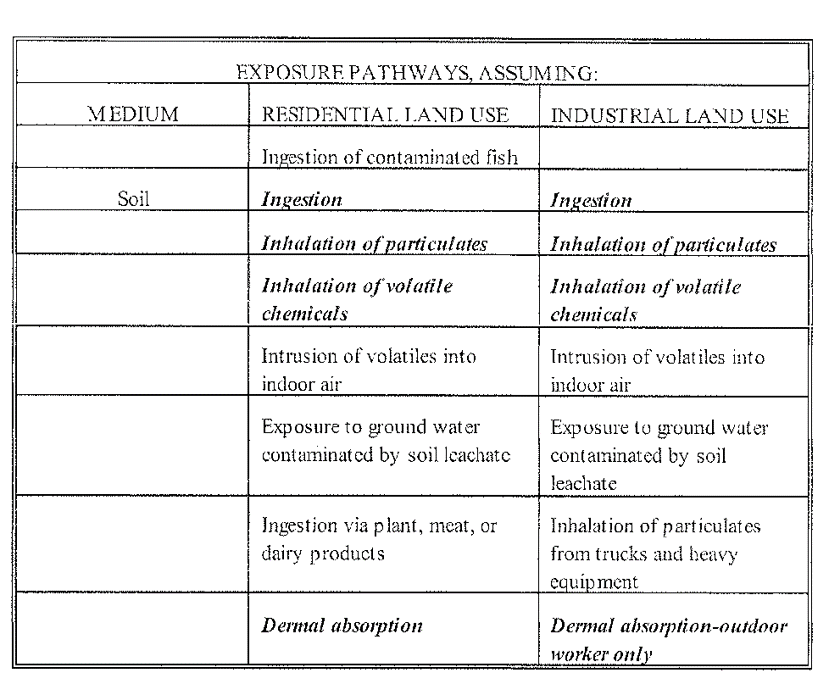

The USEPA Risk Based Screening Levels

The USEPA Risk Based Screening Levels are primary concerned with human health and do not consider impacts on animals or plants. This standard makes a different set of assumptions depending on the intended land use: for example, residential land use assumes a 24 hour a day, 350 days a year exposure time. Industrial use assumes 8 – 10 hours a day, 245 days a year exposure.

Whilst USEPA RSBLs do not address non-human health endpoints, such as ecological impacts, it serves as a useful contrast against the Dutch Standards and illustrates how multiple standards are useful in properly determining whether a site needs to be remediated.

Further Reading

For the layman, I would recommend reading the New Zealand Contaminated Land Management Guidelines for site investigation and analysis of soils.

To learn about how an Environmental Baseline Study can lead to cost savings, you can read our case study of Lorong Halus here.

We would also like to thank the Philippine Institute of Civil Engineers for inviting us to speak at their seminar.